Following the news that Sir Michael Stoute is to retire at the end of the season, look back on the achievements of the training great's top racehorses.

1= Harbinger (Timeform rating 140)

Harbinger showed clear signs of talent during his first season of racing as a three-year-old, notably winning the Gordon Stakes in the style of an exciting prospect, but it was during his four-year-old campaign that he rocketed through the ranks and put up one of the finest performances in Timeform’s history.

After decisive successes in the John Porter, Ormonde and Hardwicke in 2010, Harbinger was set his first Group 1 assignment in the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes at Ascot. It was a stellar line-up for Flat racing’s traditional mid-summer showpiece as the field included Harbinger’s stablemate Workforce – a wide-margin winner of the Derby on his previous outing – Irish Derby winner Cape Blanco and three-time Arc runner-up Youmzain.

In the event, Harbinger proved to be in a completely different league to his rivals, travelling powerfully under Olivier Peslier before unleashing a devastating turn of foot to settle the contest in a matter of strides. Despite Peslier riding with only hands and heels for much of the final furlong, Harbinger continued to roar clear of his flagging rivals, eventually scoring by 11 lengths.

A fracture of the near-fore cannon bone meant Harbinger never raced again, but there is little doubt the performance he put up at Ascot was that of an outstanding racehorse.

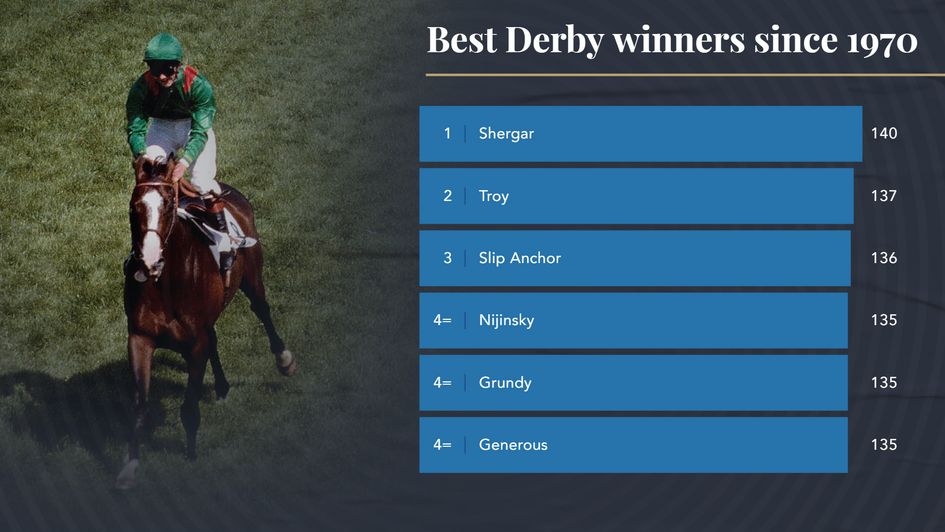

1= Shergar (140)

Shergar was an outstanding performer on the racetrack, winner of the Derby at Epsom by a record margin, but he met a tragic end.

He was head and shoulders above his contemporaries in 1981, winning the Classic Trial at Sandown by ten lengths and the Chester Vase by 12, and he started 11/10-on at Epsom.

Ridden by the 19-year-old Walter Swinburn, Shergar was sent on early in the straight and quickly set up an unassailable lead, finishing ten lengths clear of the Derby Italiano winner Glint of Gold with Scintillating Air third.

With Swinburn suspended, Lester Piggott took over for the Irish Derby and they won unchallenged by four lengths from Cut Above and Dance Bid. Swinburn regained the ride for the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes at Ascot and Shergar landed the odds by four lengths from the Prix de Diane winner Madam Gay and Fingal’s Cave.

With the Arc as his reported major objective, Shergar was rested before having a preliminary race. That race was the St Leger but Shergar suffered his only defeat of the season, finishing fourth to Cut Above and Glint of Gold, and the Arc plan was shelved.

Shergar retired to Ballymany Stud in Ireland, but after just one season there he was kidnapped in February 1983. A ransom was demanded but it is thought Shergar was killed a few days later. His remains have never been found.

3. Zilzal (137)

Zilzal was Timeform’s Horse of the Year in 1989, a year that also included Nashwan and Old Vic amongst the three-year-old crop.

Unraced as a two-year-old, Zilzal won his first five races, including the Jersey Stakes at Royal Ascot and the Criterion Stakes at Newmarket before putting up top-class performances in the Sussex Stakes at Goodwood and the Queen Elizabeth II Stakes at Ascot.

At Goodwood he started second favourite to the previous year’s winner Warning but ran out a three-length winner in a strongly-run race from Green Line Express and Markofdistinction. That led to a clash between Zilzal and Polish Precedent at Ascot. Polish Precedent had won all seven of his races during the year, including the prestigious double of the Prix Jacques le Marois and the Prix du Moulin de Longchamp, but Zilzal started favourite at evens with Polish Precedent 11/8. It was 10/1 bar the two. Zilzal made all and beat Polish Precedent hands down by three lengths with a further two lengths back to the Celebration Mile winner Distant Relative in third.

Always a free sweater, Zilzal boiled over before the Breeders’ Cup Mile at Gulfstream in November and lost his unbeaten record. Last away, he was never able to get back on terms, finishing sixth behind Steinlen. He was retired to stud in the USA.

4= Shadeed (135)

Shadeed was a highly-strung individual who overcame problems to win four of his seven races, notably the 2000 Guineas at Newmarket and the Queen Elizabeth II Stakes at Ascot in 1985.

Successful once as a two-year-old, Shadeed couldn’t have been more impressive when winning the Craven Stakes on his reappearance by six lengths from the subsequent Sandown Classic Trial and Dante winner Damister. This performance ensured that Shadeed started odds-on for the 2000 Guineas and he obliged, but only by a head from the Greenham Stakes winner Bairn after Shadeed had become very excitable during the parade.

Shadeed’s next race was in the Epsom Derby, for which he had been winter favourite, but he proved most intractable in the early stages and ran deplorably. He later went down with an illness, the effects of which kept him off the racecourse until the autumn.

Stoute performed a fine training performance to bring Shadeed back to top form and the colt established himself as the season’s top miler in the Queen Elizabeth II Stakes. In a very strongly-run race, Shadeed took over the lead just before halfway and kept up a blistering gallop. Despite tiring in the closing stages, he still broke the course record and had two and a half lengths to spare over the Arlington Million winner Teleprompter with Zaizafon and Bairn next.

Shadeed finished his career with a below-par fourth, promoted to third, with no excuses, behind Cozzene in the Breeders’ Cup Mile at Aqueduct.

4= Shahrastani (135)

Shahrastani was one of the best of an outstanding bunch of three-year-old colts in 1986. He won both the Derby at Epsom, where he inflicted the only European defeat of Dancing Brave’s career, and the Irish Derby, which he won in scintillating fashion by eight lengths.

He was only second on his sole outing as a two-year-old but won both the Classic Trial at Sandown and the Dante Stakes at York before starting second favourite to Dancing Brave at Epsom. There he was given a splendid ride by Walter Swinburn, who was, as ever, perfectly poised round Tattenham Corner, getting first run on Dancing Brave and holding on by half a length from the fast-finishing runner-up with Mashkour two and a half lengths back in third. Dancing Brave’s jockey, Greville Starkey, had been trying to preserve his mount’s stamina but received plenty of criticism for his ride, and Shahrastani was thought to have been a lucky winner.

With Dancing Brave going to Sandown for the Eclipse, Shahrastani started evens favourite for the Irish Derby and more than justified his billing, finishing well clear of the King Edward VII Stakes winner Bonhomie with the Prix du Jockey Club third Bakharoff third and Mashkour fourth. There could be no doubt this was a top-class performance.

Dancing Brave and Shahrastani were the only three-year-olds to contest the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes at Ascot, and while Dancing Brave gained a second successive win against older horses, Shahrastani disappointed, finishing fourth, nearly ten lengths behind the winner.

While Shahrastani was syndicated before the King George, he still contested the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, his only race after Ascot, and he finished a creditable fourth to Dancing Brave in one of the strongest fields to have contested the race, beaten just over two lengths by the winner, with Bering and Triptych also ahead of him. He was retired to stud in Kentucky.

4= Shareef Dancer (135)

Shareef Dancer’s career lasted only five races and he was beaten on his second and third outings, but he was much improved at a mile and a half on firm ground on his last two, winning the King Edward VII Stakes at Royal Ascot and the Irish Derby at the Curragh in 1983.

The field at the Curragh was a strong one, containing the first two from the Epsom equivalent, Teenoso and Carlingford Castle, the Prix du Jockey Club winner Caerleon, and the Irish 2000 Guineas winner Wassl. Shareef Dancer was tremendously impressive, pulling his way into the lead two furlongs out, putting the issue beyond doubt in a few strides and drawing away to win by a long-looking three lengths from Caerleon with Teenoso a further two lengths back in third, although the former had been forced to switch after being trapped on the rail early in the straight.

Shareef Dancer didn’t race again and his early retirement caused plenty of controversy. He was withdrawn from the Benson and Hedges Gold Cup (now the International Stakes) because the going was deemed to have become unsuitable after morning rain, with the race being won by Caerleon. Shareef Dancer was taken out of the September Stakes at the overnight stage (reportedly because of an adverse weather forecast) and he also missed the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe. Shareef Dancer was syndicated for $40m, having seen less than ten minutes of action on the racecourse.

7. Pilsudski (134)

Pilsudski was successful on only three of his first ten races, but he progressed into a top-class performer, as tough and genuine a racehorse one could find, winning six Group 1 races and twice finishing second in the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe.

After winning the Grosser Preis von Baden, his first Group 1 success, in 1996, Pilsudski went on to finish second to Helissio in the Arc before winning a strong renewal of the Breeders’ Cup Turf at Woodbine by a length and a quarter from stable-companion Singspiel (who won the Japan Cup on his next start), Swain and the St Leger winner Shantou.

Pilsudksi improved again the following year, winning the Eclipse Stakes at Sandown (beating Bosra Sham, who suffered trouble in running), the Champion Stakes at Leopardstown (by four and a half lengths from the Irish 2000 Guineas/Derby winner Desert King), the Champion Stakes at Newmarket and the Japan Cup at Tokyo. Sandwiched in between those performances were second places in both the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes at Ascot (beaten a length by Swain, with Helissio and Singspiel filling the frame) and the Arc (five lengths behind the outstanding Peintre Celebre). He was retired to stud in Japan.

8= Crystal Ocean (133)

Crystal Ocean will be best remembered as an exceptionally tough, consistent horse with a tremendous constitution, but it should not be forgotten that he also possessed rare ability.

Like so many from the yard, Crystal Ocean was handled patiently during his classic campaign, signing off with a meritorious second in an extremely strong renewal of the St Leger, in which he was beaten by Capri but finished in advance of Stradivarius, Rekindling, Coronet and Defoe among others.

Arguably his best effort at four also came in defeat, when he was agonisingly overhauled by stablemate Poet’s Word in a thrilling finish to the King George, but he raised his game further at five, finally gaining a deserved breakthrough at the highest level when beating Magical and Waldgeist – subsequent winners of the Champion Stakes and Arc respectively – in the Prince of Wales’s Stakes at Ascot.

His most iconic performance, however, was when narrowly beaten by Enable in the 2019 King George. He pushed the dual Arc winner – who was receiving 3 lb – all the way in a race for the ages, enhancing his reputation despite losing by a neck.

8= Marwell (133)

Marwell was one of the best fillies of the 1980s. She was unbeaten in five races as a two-year-old, including the Cheveley Park Stakes, and won a further three Group 1 races the following year.

Although beaten three times in 1981, the first of which came in the 1000 Guineas won by Fairy Footsteps, Marwell enhanced her reputation when returned to sprinting, winning the King’s Stand Stakes at Royal Ascot, the July Cup at Newmarket and the Prix de l’Abbaye at Longchamp. She was an impressive winner of the July Cup by three lengths from the 1980 winner Moorestyle, but was beaten on her next two starts, in the William Hill Sprint Championship (the Nunthorpe) at York, where she finished second to Sharpo, and in the Vernons Sprint Cup at Haydock (caught close home by Runnett).

However, she finished her career in the Prix de l’Abbaye, gaining revenge for her previous two defeats, hanging on exceptionally gamely by a neck from Sharpo with Runnett back in fifth.

At stud Marwell produced two Group 1 winners, notably Marling, who was the best three-old filly over a mile in 1992 with successive wins in the Irish 1000 Guineas, the Coronation Stakes and the Sussex Stakes.

8= Singspiel (133)

After finishing an encouraging fifth on debut at Leicester – a course Sir Michael Stoute likes to introduce promising types at – Singspiel would finish outside the first two only twice from 20 starts, showing admirable consistency and tenacity.

Victory in a three-runner listed race on the final outing of the campaign was his only success as a three-year-old, but he had shown himself capable of cutting it at the highest level, finishing runner-up to Halling in the Eclipse, and he went on to make his top-level breakthrough in the Canadian International at Woodbine the following season.

He was unable to fend off stablemate Pilsudski in the Breeders’ Cup Turf over the same course and distance a month later, but he soon bagged another big prize by landing the Japan Cup on his final outing in 1996.

Up to that point in his career Singspiel’s record in the big races outstripped his rating, but he would take a jump forward in form terms as a five-year-old. He landed the Dubai World Cup on his return, followed up in the Coronation Cup and, having disappointed in the King George, he produced the performance of his career to win the Juddmonte International, bringing his earnings to an astonishing £3,600,000.

8= Workforce (133)

There were a couple of notable disappointments during Workforce’s career – including when well below his best behind stablemate Harbinger in the King George – but there were also some astonishing highs, and performances of rare merit.

His seven-length success in the Derby - achieved in a course record time - was the greatest winning margin in the race since Shergar spread-eagled his rivals in 1981. And he ran to the same level when landing the Arc, becoming, at that time, just the sixth colt in history to land that notable double.

He strode majestically clear on fast ground at Epsom, but proved his versatility – and resolve – by digging deep on much softer going at Longchamp, prevailing by a head. It’s also worth noting that he hardly enjoyed the ideal build up to the Arc, arriving on the back of his King George flop more than two months earlier.

He was ultimately underwhelming during his four-year-old campaign, failing to score at the highest level, but that does not diminish his achievements at three.

More from Sporting Life

Safer gambling

We are committed in our support of safer gambling. Recommended bets are advised to over-18s and we strongly encourage readers to wager only what they can afford to lose.

If you are concerned about your gambling, please call the National Gambling Helpline / GamCare on 0808 8020 133.

Further support and information can be found at begambleaware.org and gamblingtherapy.org.