For many, the evolution of golf data has changed the game. For most, it has at the very least helped to colour it. With every passing season, our understanding of how things happen has improved, for those who want to know. Some may well be happy sticking to the old words but there can be no doubting the benefits of studying the new numbers, too.

The best reason for ignorance is that change equals challenge. When the information you've relied on suddenly seems empty, it can be disorienting. It calls to my mind Jose Mourinho: once the revolutionary successor to Sir Alex Ferguson, some would say he's now been left behind, victim of the gegenpress. It seems impossible to believe, but one day we might say the same of Pep Guardiola or Jurgen Klopp.

For the television pundit, it remains to be seen at what cost, if any, one ignores the changing landscape, and it should be said that most embrace it. For the golf tipster, feedback comes weekly in the starkest form and, for this particular one, it has been and remains difficult to know where to draw the line. It seems to me to be eminently possible that exhaustive data combined with a words-over-numbers background can make for a messy combination. Nor do I believe you have to be a data whizz to have a chance in this game.

All of which is an admission: that in digging through the data which helps illustrate the 2021 European Tour season, I do not have the necessary skills to perform the checks and balances which would make for genuine insight in this area. For that sort of thing, I recommend DataGolf, Rick Gehman, Fantasy National and sgtee2green. Nevertheless, it has been illuminating for me, and I hope it will provide one or two points of interest for you, too.

New (short) post: a fun look at how Bryson DeChambeau's skill profile changed after chasing, and finding, club head speed. https://t.co/333DLiep1v pic.twitter.com/u0KBFM1iRP

— data golf (@DataGolf) January 3, 2022

The (DP) world is changing

It should be said that strokes-gained data on the PGA Tour is available from 2004 onwards, back-dated via the shot-tracking technology which means that no longer is the television the best place to know how the ball got to the hole.

On the European Tour our library is much thinner and, as it evolves to become the DP World Tour, strategic alliances all over the place, it's only in time that we'll be able to piece things together with any degree of confidence. For that reason, this article really ought to have waited a few years. In fact the single biggest caveat is that while we've tens of thousands of rounds and hundreds of thousands of shots to measure, that's still a small sample within the context of this sport.

While the PGA Tour close in on two decades, 2021 was the first full(ish) campaign for which data was reliably gathered and shared in Europe. Two years earlier, the first tentative steps relied solely on caddies and their estimations and, with the greatest of respect to them, you don't need a degree in data science to hear alarm bells. Just the other day I watched a player putt from 11 feet, as an on-course commentator guessed the distance to be six. Now apply that to every shot in a low-key event which isn't on television, and you'd expect the data to be a mess. Perhaps this explains why the Tour has taken it off its website.

In 2020, this process continued while work went on in the background until, at the BMW PGA Championship, the shot-by-shot era began in earnest. Since then (and with one or two exceptions), we've been able to follow IMG's shot tracking, and analyse their data. At some stage, I hope that the Tour itself, or somebody from The Internet, is able to put it all together and provide us with analytics tools like those you'll find at Fantasy National and DataGolf. For now, you have to make do with an essay by me, which is terrible luck.

The process, such as it is

The data I've looked at covers every player finishing T10 or better, later broken down by event, to give a snapshot of what might have been particularly important on a particular week at a particular course. The basic intention of this is to demonstrate where you simply couldn't get away with a bad week with the driver, or where short-games didn't matter too much. I'll stop stressing this point about the sample size after this sentence, but first: none of this is done with the ambition of drawing firm conclusions. There is not enough data.

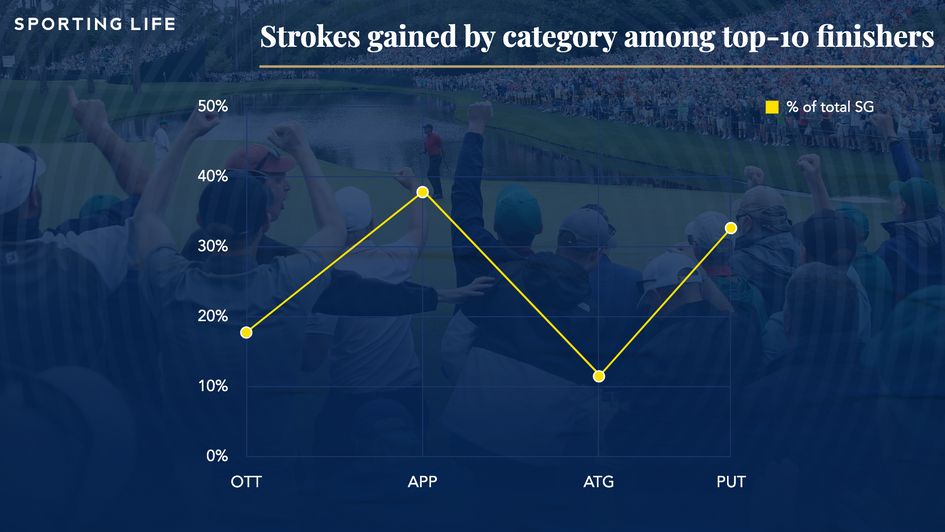

Doing so reveals exactly what you'd expect when it comes to the sport as a whole, which is to say that approach play is king, and putting is next. Across 28 events, 37% of total strokes-gained came from approach shots, 33% from putting. The remaining 30% is split between tee shots (on par-fours and par-fives) and around-the-green work, almost two-thirds of that from the tee and the rest in the short-game. The data this is based on might lack depth, but it supports all that we've come to know about golf at this level.

It stands to reason that around-the-green should matter less than anything. Think about how those shots are played, and how often. Drives can go out of bounds or into hazards; chips generally do not. Elite players do not miss that many greens, and may require two or three around-the-green shots per round. The three other departments account for the vast majority of a player's total shots.

The elephant in the room

Putting.

If there's one aspect of golf analysis which is especially divisive, it is putting. The numbers here confirm that to win golf tournaments typically requires good putting. In fact, the only player who won on the European Tour putting objectively badly in 2021 was Dustin Johnson, when the then world number one won back his title in Saudi Arabia.

When you read articles like mine that brush putting aside, perhaps they ought to provide a clarification: nobody worth listening to will tell you putting doesn't matter. They might, however, tell you that putting is far more volatile than ball-striking, and therefore putting stats are far less useful as a predictive tool. We saw as much at the Sony Open, where Stewart Cink led the field in putting at halfway having been poor a week earlier, and where come the end of the week Hideki Matsuyama had transformed his putting to win. Matsuyama's turnaround from the previous week was in excess of 2.25 shots per day, more than nine for the tournament.

This convenient example does not exist in isolation. Nor is it used as an attempt to dismiss attempts to predict putting in so far as anyone can. Changes in grass types and green speeds can help, and there are players who get hot and stay hot. There is also so much more to be learned beyond numbers – perhaps a transcript would reveal that Cink has gone back to an old putter, and perhaps that might help him to sustain this putting through his next start. Where Matsuyama is concerned, how do you assign a value to the confidence he gained at Augusta last April?

It's been said that 'the winner is the best putter among the best ball-strikers that week'. This is rarely true in a literal sense, but it is a sentence which I believe does provide a sufficiently accurate guide. Put another way, it is exceptionally rare for a player to win a tournament when relying almost totally on their putter. But when someone who is hitting the ball well also putts well, there you have a likely candidate. Conversely, it is far more likely a player hitting their ball to a high standard might compete despite putting poorly, and so we return to why it is not to be dwelt on.

Can ride a hot putter to victory. But great ball-striking will give you more opportunities to win.

— Sean Martin (@PGATOURSMartin) September 17, 2018

The winner is often the best putter among the best ball-strikers.

Problems off the tee...

By contrast, driving in general is more predictable, and perhaps this justifies greater focus on it – even when the data says good putting is a better route to good performance on any given week. It seems reasonable to suggest who might drive the ball well. More difficult is to know for whom the putts will drop.

Given that he played almost twice the number of rounds of the top-ranked Garrick Higgo, it's fair to label Joakim Lagergren as the best putter on the European Tour in 2021, just ahead of his compatriot, Alex Bjork. Lagergren was consistently above-average, but he wasn't consistent: his three best performances were spread far apart, each of them followed by a considerable downturn, and he threw in a genuine shocker for good measure.

Laurie Canter was the best driver on the circuit in 2021. In contrast to Lagergren, not only did he not have a horror week at any stage (the most he lost per-round in an event was less than a quarter of a stroke), but if he drove well one week, chances are he drove well again the next. That Canter was also the best driver in 2020 underlines his greater consistency, and speaks to driving's greater predictability.

Not that volatility is in general a bad thing. In fact, quite the opposite. My view on Collin Morikawa, for instance, is that while he is a moderate putter by the numbers, he also does something those with similar season-long stats do not, and putts brilliantly on occasion. Chez Reavie was statistically a better putter than him last season, but never over four rounds did he get close to the putting Morikawa produced when winning the WGC-Workday. The season before, Morikawa was in fact the best putter in the field when winning the US PGA, something Reavie last achieved in 2012.

Back to tee-shots, and I was a little surprised they didn't contribute more towards top-10 scores in 2021. Nevertheless, the good drivers were generally predictable; the good putters far less so.

And now for the prize ceremony

At this point, my intention was to tease more with the promise of weekly charts in betting previews, and keep some findings to myself for now. Down with that idea. Instead, here are four tables, highlighting the top 10 tournaments by importance of statistical category, in the usual order: driving, approach play, short-game, and putting. After that, I've picked out five potentially significant notes.

Five takeaways from 2021...

You can lose ground around the greens (almost) anywhere

There were nine tournaments in 2021 where nobody in the top 10 lost strokes with their approaches, and many more where one or two players bucked the trend. Nobody got particularly close to winning with bad iron play. By contrast, there were three winners who lost strokes around the green, and just two tournaments where those with iffy short-games were locked out. They came at courses with their own extremes: Royal Greens, and Valderrama.

Royal Greens isn't all about blasting it off the tee, but it helps. We saw as much during the first renewal, when Dustin Johnson was able to whack his ball at par-fours without fear of what might go wrong. Hao-tong Li recorded four eagles in a single round and length was a massive advantage. It will remain that way unless the wind blows, for those following the lucrative Asian Tour event there in February. Just recently, Bryson DeChambeau stated that the course sets up particularly well for him.

Valderrama is everything that Royal Greens is not: short, tree-lined, with small greens and rich heritage. It's a course where driver isn't just dangerous, it is at times simply not an option. I would wager that there is no other DP World Tour venue which sees the club reached for less frequently. Tee shots were important, but driver was not.

What these courses have in common is that sharp short-games have been vital, but with Royal Greens off the schedule for good, we can focus on Valderrama and state with confidence that a dynamite short-game is more valuable here than just about anywhere. It was the only course in 2021 at which more than 20% of the top-10 finishers' strokes were gained around the greens.

It's worth remembering that those playing well, i.e. those who've been analysed here, will have tended to require their short-games less, and that means less volatility, less variation, and less importance. But at Valderrama, even the best long-games can't avoid putting pressure on short-games. No wonder the likes of Soren Kjeldsen and Graeme McDowell used to thrive here, nor that Sergio Garcia has never failed to play well.

The data alone isn't necessarily emphatic, but the tournament's history is. Whoever wins there in the autumn, expect them to have shown silky skills around the greens (along with a high degree of accuracy, quality approaches, that good putting week we usually need, and a steely resolve). You know, someone like Matt Fitzpatrick.

Passing of the baton, or should that be tee-peg?

In September 2019, Sergio Garcia had to fend off a youngster with some familiar qualities to win the KLM Open. That youngster was Nicolai Hojgaard who, two years later, went on to confirm his abundant potential by beating Tommy Fleetwood to win the Italian Open.

Like Garcia, Hojgaard will go on to build his career on quality ball-striking, with driver in particular looking like his key weapon. Like Garcia, he was among a select group of players who gained more than six strokes off the tee during a tournament on the European Tour last year.

The difference is Hojgaard won. He was in fact one of just two champions all season to base victory on driving and gain the largest share of their strokes off-the-tee. That probably tells us something about Marco Simone, a big, modern, Ryder Cup course where Adrian Meronk finished T2, but it tells us more about the player.

The sky is the limit.

We remember the putt, but don't forget the drives!

Just as we can contrast Royal Greens with Valderrama, there's not much that Marco Simone and Karen Country Club have in common. The former is a large, purpose-built tourist destination near Rome, created for the Ryder Cup which it will host next year, and where there could yet be 'only two Hojgaards' in the European line-up.

Karen is an old course in Nairobi, lined with trees and with thimble greens surrounded by bunkers filled with clay-coloured sand. If Marco Simone is manicured, then Karen is rugged, within which lies much of the charm.

Yet just like Marco Simone, it provided the platform for a champion who won because of his driver. It's easy to overlook it if, like me, you leapt from the sofa when Daniel van Tonder holed a monster putt to effectively force a play-off he'd go on to win, but van Tonder produced the standout driving performance of the season, gaining almost seven and a quarter strokes off the tee. For context, DeChambeau topped that figure just once in 2021.

This might be the best example yet of overlaying what you can see with what you can download. Karen Country Club can be conquered many ways, and is not necessarily a bombers' paradise. However, it is vulnerable should a player like van Tonder decide to attack, and then enjoy a little luck along the way, with at least three par-fours which can be driven, and many corners which can be cut.

It's not on the schedule for 2022, but while Muthaiga has its own quirks, we may yet find that it provides a similar challenge and with that a similar outcome.

One course that does remain on the list is Bernardus, which threw up surely the shock of the year as Kristoffer Broberg secured an emotional victory to draw a line under years of injury frustration.

Broberg was the only European Tour winner in 2021 who lost strokes off the tee, and if you remember Bernardus, you might remember why exactly the Swede was able to get away with his typically errant driving there. Fairways were extraordinarily wide, and if you missed one you often landed on another at an exposed course where the main challenge was on approach to contoured greens with steep run-offs.

Not for the first time, a wide-open course took away the advantage of good drivers, and allowed a hitherto lost soul to find his game. Or else, to find the one place that game could be explosive.

An elite American approach-play performance

The best display of approach work in 2021 saw a talented young American gain more than three strokes per round with his irons. It was astonishing. And it was not Collin Morikawa.

No, the man in question was Chase Hanna, who dazzled with his ball-striking throughout a devilish string of sixth-placed finishes during summer. It's likely that in gaining a total of 12.6 strokes with his approaches in the Hero Open, Hanna produced figures he'll never match. After all, Morikawa *caveats klaxon* is yet to turn it up to 11 himself.

And yet, having again showed his iron play to be his strength when starting the season well in Joburg, Hanna looks one to keep on the right side of, especially when the Rolex Series makes way for the meat-and-drink grind from mid-February onwards.

Drive to survive

I'll end by reminding you all how fickle and flimsy this is, and the best way I can sum that up, I think, is to reveal that driving was less important at Green Eagle than anywhere else last year. Yes, the event was reduced to 54 holes, but this was still surprising.

Green Eagle is one of the hardest courses on the circuit. It's also one of the longest and, one way or another, it is certainly the most confounding. This behemoth is where Richard McEvoy, one of the shortest hitters around, won his sole European Tour title. It's where Ashley Chesters, the most accurate driver and far from the longest, has found real comfort.

But it's also early days. When we get to the Porsche European Open, I expect I'll convince myself that we'd all be better off siding with those who get the ball out there, like Paul Casey, like Jordan Smith, who've also won in Hamburg. Like Adrian Meronk, the Polish player who was in fact born in Hamburg. In the long run, long hitters may underline the point of all this: it's early days.

Three-thousand words and I think I still like the anecdotes best for now. Good luck this season.