Fast Results

Fast Results Scores

Scores

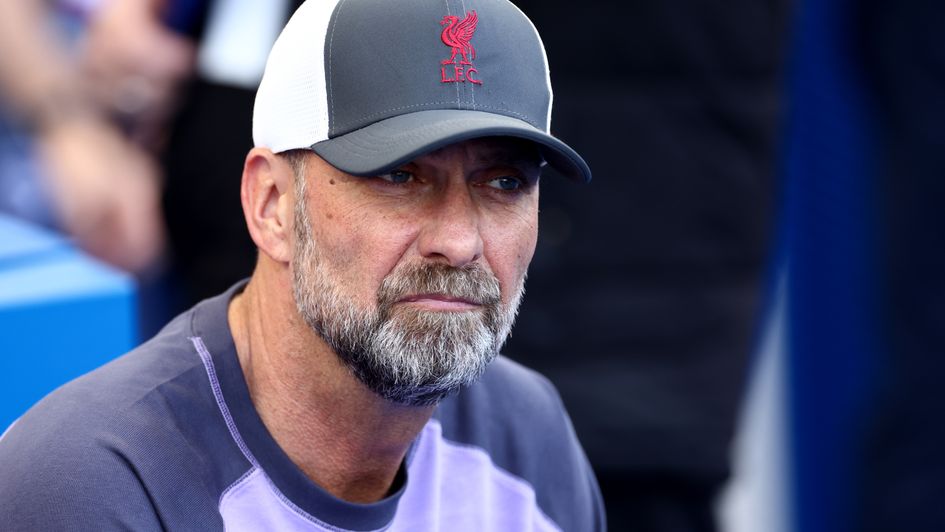

Jurgen Klopp's Liverpool: Reds rebooted and ready or a rethink required?

If you need evidence that Liverpool are synonymous with a weird and wild opening salvo of this Premier League season then how about Opta’s xG modelling of an ‘expected points (xP)’ table – which has Jurgen Klopp’s side just behind Everton.

- Published before Liverpool 2-0 Everton

These things should be taken with a pinch of salt but sitting below their local rivals, albeit in a table based on metrics not results, conforms to the impossibility of pinning Liverpool down; to the cognitive dissonance that is watching them this season.

Klopp called them “Liverpool 2.0” back in September but that definition would suggest the reboot is complete.

Instead they are more like a newly-refreshed team striving to break out of the decaying old one.

Dominik Szoboszlai's brilliance offset by clumsy Virgil van Dijk errors; a vibrant 3-box-3 formation crumpling as Andrew Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold strive to understand their new roles.

Klopp going back to the start

But step back a little and what’s most interesting about 2.0 is its similarity to the beginning of the Klopp era, both in tactical methodology and general vibe.

For the first couple of years at Anfield, Liverpool 1.0 were a disorderly mess, fun to watch but far too open defensively and too straight-lined in their attacks to dominate matches as they needed to do.

Things only stabilised once Klopp borrowed calmer methods from Pep Guardiola and added loadbearing pillars Fabinho and Van Dijk, at which point Liverpool finally clicked into gear and became almost unbeatable, just as Borussia Dortmund had done previously.

In 2023/24 the cycle has seemingly begun again, except this time there is expectation things will fall into place a lot quicker, despite Liverpool clearly lacking exactly the same kinds of players and in the same positions.

For all the midfield purchases over the summer, Fabinho has not been replaced and Van Dijk clearly isn’t the player he once was.

It leaves Liverpool as ropey, stretchy, and prone to meltdowns as they were when Klopp was the ‘heavy metal’ gegenpresser seemingly embracing chaos over half a decade ago.

Full-back flexibility: fashionable folly?

Back then, Liverpool’s great strength was Robertson and Alexander-Arnold, but their old role as flying full-backs has now been fully abandoned for Klopp’s second act, in keeping with the Europe-wide trend of reinventing the position.

Alexander-Arnold inverts into central midfield and Robertson becomes a left centre-back as Liverpool’s shape morphs into a 3-2-2-3 with a box in the middle of the park. It is… ok.

At times the extra man in the middle allows Liverpool to build sharply with one-touch football, brings control of possession, and allows for a barrelling front five to take the opponent apart.

But, just as often, it leaves Liverpool open to being counter-attacked down the flanks. Alexander-Arnold’s side is often left open, his one-on-one defending more exposed than ever now he has two competing roles in the team.

As for Robertson, who still has licence to occasionally roam forward, his position in a back three seems to be undermining Van Dijk and Ibrahima Konate, who are often scrambling across the width of the pitch.

Alexis as Anfield anchor not working

Premier League teams are increasingly aware of where to target Liverpool and how to break beyond a midfield that lacks a true defender, which suggests the situation will only get worse as long as Alexis Mac Allister is the man tasked with anchoring the side.

That at least partly explains the four red cards in eight games, the mid-table-worthy 11.5 expected goals against (xGA), and the five errors leading to shots, more than anyone bar Bournemouth and Burnley.

And until that is fixed, it’s likely that Liverpool won’t be able to dominate possession and territory like they did at their peak, in turn reducing the calm patterns of attack that are needed.

That is why so often this season Liverpool have won matches simply by throwing the kitchen sink at a problem, moving to an erratic front four that has served as a battering ram against Newcastle, Wolves, and West Ham in particular.

Fab front-line helps with finding formula

The counterpoint to that argument, however, is that Klopp is waiting for the fire and the fury of his new-look attacking line to start scaring the opposition into retreat.

Mohamed Salah, Luis Diaz, and Darwin Nunez are a sight to behold, and as Klopp doubles down on attacking dynamism like never before, the hope perhaps is that teams will sit deeper: that psychology will shift the tactical battle back towards territorial control.

To a certain extent that is what happened when things fell into place in 2018/19, although the Fabinho factor is a glaring, unavoidable problem.

If it wasn’t for the last-minute Joel Matip own goal at Tottenham, Liverpool would be 19 matches unbeaten in the Premier League.

In the last half-season run they have won 42 points, which is just two points short of the average required to equal Manchester City’s title-winning total of 89 last season.

Man City appear weaker than they were in 2022/23. Liverpool are three points off the top.

These are all good reasons to think Klopp has time to find the right formula this season and put together a serious title challenge, perhaps by integrating Wataru Endo and hoping he is the answer.

But last time Klopp had to start from a base this chaotic, this unwieldy, it was two-and-a-half years until they were even ready to begin.

More from Sporting Life

Safer gambling

We are committed in our support of safer gambling. Recommended bets are advised to over-18s and we strongly encourage readers to wager only what they can afford to lose.

If you are concerned about your gambling, please call the National Gambling Helpline / GamCare on 0808 8020 133.

Further support and information can be found at begambleaware.org and gamblingtherapy.org.