Rabid anger is the cultural tone most feared, and most lived, by England managers through the ages and yet nothing is quite as damning as apathy.

- Alex Keble (@alexkeble) is a football journalist who specialises in tactical understanding, analysis and predictions of all aspects of the game

The Gareth Southgate era has always had such clear definition but since defeat to France in Qatar the thing has bobbed about, untethered, with all the narrative urgency of an epilogue.

And there are so many reasons to believe the party’s over.

Harry Kane’s missed penalty and the World Cup quarter-final exit was the perfect ending: a glorious failure with echoes of Southgate’s Euro 96, but also a loss remarkable for being unremarkable, the absence of jingoistic recriminations upon defeat a testament to the cultural shift Southgate has overseen.

So obviously was it the end of the story we’ve even had a celebrated play at the National Theatre, Dear England, providing a retrospective on Southgate’s time in charge.

When artists are writing your obituary surely your time is up.

England taking backwards steps

But if that didn’t make it clear, then the collective eye-roll at his squad announcements surely have.

Where once there was hope of evolution towards a progressive and dynamic England line-up the presence of Harry Maguire and Jordan Henderson in the camp now elicit little more than a shrug - England’s equivalent of the Conservative Party’s policy to “let Rishi be Rishi” as they wait for oblivion.

Letting Gareth be Gareth has inevitably meant a doubling down on the principles we once hoped were only temporary but also, more surprisingly, a weakening of the statesmanlike persona, which appears to suggest Southgate is no longer fighting, no longer straining for approval, no longer on a path that’s leading to anywhere in particular.

“I don’t really know what the morality argument is because so many of our industries are wrapped up with Saudi investment,” Southgate told reporters last month as he sought to justify Henderson’s inclusion. “Given the situation with Russia we are reliant on Saudi Arabia for a lot of our oil.”

That is a very one-sided take, to say the least, as was his dismissive batting away of questions on Saudi Arabia’s treatment of the LGBTQ+ community.

“It’s very difficult to work through all that,” he said. “So until somebody tells me differently on whether I can or can’t pick players if they’re playing in different countries … My job is to pick a football team. I don’t think you can pick a football team based on any prejudice about where they might be playing their football. I am a bit lost with some of the questioning.”

Southgate has changed

Beyond the dubious ethics and moral whataboutery here, it just doesn’t sound like the careful and considered Southgate who transformed how English football sees itself.

Indeed he was spiky, coming across as a man at the end of his tether; no longer thinking holistically about his role, or how to help shape the relationship between the England men’s team and the wider culture.

There is a neat symmetry here to the footballing side of his squad selection, which again this month has included Henderson and Maguire, two of the nine players who will be over 30 by the time Euro 2024 gets underway next June.

The push for Southgate to open up a little more, to let an unusually gifted generation flourish creatively, has always been a little overstated. Knock-out tournaments are won through conservatism and Southgate is right not to attempt adventurous tactics with a squad he only gets to see once every couple of months.

But like France in 2018, England are surely now in a position to use progressive players in more regressive roles, instructing tactically-savvy young footballers to choose their moments within a framework that doesn’t sacrifice defensive solidity yet still offers the chance to overwhelm opponents; to accelerate when the time is right.

A refusal to evolve

As ever with Southgate, the problem is central midfield and central defence: the epicentre of the stodge that clogs up his teams. Again, Henderson and Maguire are the totems, living statues and monuments to the age of Gareth: players cast off by their elite clubs but clung to by an England manager no longer looking ahead.

And he has options. Ezri Konsa should be in the squad, although with six centre-backs Southgate could afford to drop Maguire without replacing him, freeing up space for more midfield options to challenge Henderson.

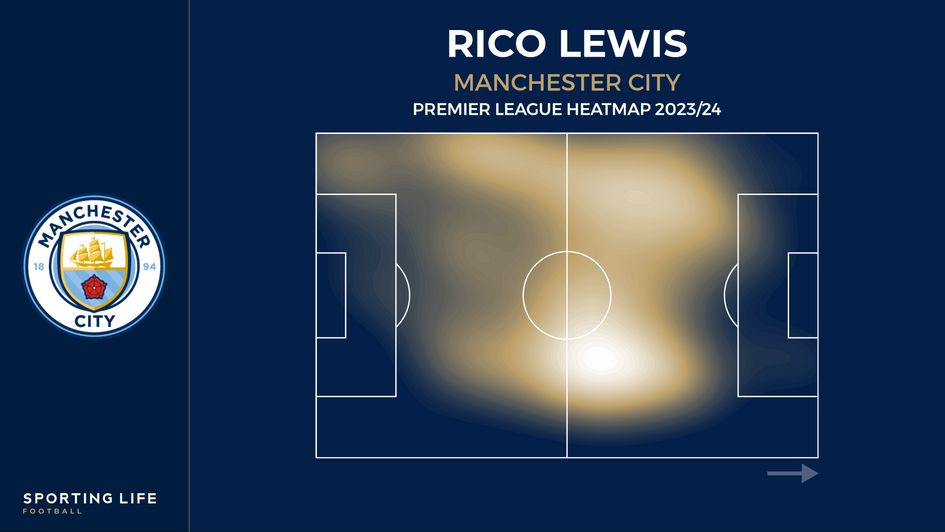

Jacob Ramsey, Curtis Jones, Carney Chukwuemeka and Rico Lewis are all ready for the call-up; ready to play in a more elastic, athletic, and assertive England midfield alongside Declan Rice and Jude Bellingham.

Those would be the progressive selections, indicating forward momentum, building for the future, planning… something. Instead, Southgate is looking inward, giving in to his most conservative instincts at the precise moment he ought to be laying a foundation for whatever and whoever is to come next.

A sad decline for a successful stint

Southgate has been a magnificent England manager and easily the best since Sir Alf Ramsey. He should be viewed as a national treasure and history will undoubtedly be kind to him; to the extraordinary feat of detoxifying the culture and reconnecting England with its men’s team at a time of polarising national politics.

He still does not get enough credit for that - or even for the more tangible, stick-to-football achievement of reaching a World Cup semi-final and being a penalty shootout away from winning a major tournament.

But as we laze through a postscript even Southgate very nearly decided against, it is sad to see that his final year in charge seems more bogged down than ever in a loyalty part-fuelled by fear of opening up and by the instinct to retreat.

It is the instinct of Gareth being Gareth: a project turning inwards, minds closing down, and a disappointing moral decline that hammers the final nail for an era already over.

More from Sporting Life

- Fixtures, results and live scores

- Expert xG analysis and features

- Transfer news and done deals

- Football and other sports tips

- Download our free iOS and Android app

- Podcasts and video content

Safer gambling

We are committed in our support of safer gambling. Recommended bets are advised to over-18s and we strongly encourage readers to wager only what they can afford to lose.

If you are concerned about your gambling, please call the National Gambling Helpline / GamCare on 0808 8020 133.

Further support and information can be found at begambleaware.org and gamblingtherapy.org.